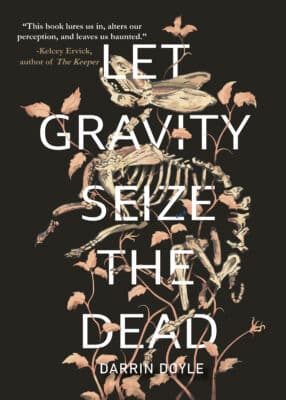

If you’re venturing into the woods this summer to go camping or hiking, the perfect companion book might be Darrin Doyle’s latest, Let Gravity Seize the Dead. Doyle excels at bringing the natural world alive with electric prose and imagery that conveys the beauty and occasional menace of the forest. Let Gravity Seize the Dead has echoes of William Faulkner, Stephen King, and Raymond Carver, but above all the book is Darren Doyle at his original best.

Order your copy here.

Doyle shared his thoughts in a recent interview with Cease, Cows.

Chuck Augello: If a potential reader picks up a copy of Let Gravity Seize the Dead, what should they expect?

Darrin Doyle: They should expect an intense experience – a lean, propulsive story with a spooky, unsettling atmosphere. This book isn’t about jump scares; it’s about a growing sense of dread and unease. It’s about exploring liminal spaces, the spaces in-between states of being: between life and death, the familiar and the unfamiliar, civilization and nature, good and evil.

CA: Tell us about the book’s genesis. What led you to write this story?

DD: I’ve always loved the woods and try to spend time there whenever I can. There’s a rustic cabin in Wilderness State Park that I like to rent each summer. It’s completely isolated from other people, and with no electricity it’s an excellent way to unplug and focus on writing in a notebook, sitting by a campfire as night falls. This Michigan forest became a real inspiration in my previous novel, The Beast in Aisle 34, and it continues with this book. The cabin is located two miles down a narrow, one-lane path, only wide enough to fit a single vehicle. It takes about 25 minutes to get to the cabin because the path is so lurching, and you have to proceed very slowly. This narrow path became the opening image of the story as I imagined a modern family moving to a run-down cabin built 100 years earlier by their ancestors.

CA: One of the central characters is Beck Randall, who buys the abandoned family cabin from his tax attorney father and return to the property. What interested you in this character and his journey?

DD: It’s long been my fantasy to disappear into the wilderness. I used to love the TV show Grizzly Adams, in which a man is accused of a crime he didn’t commit, so he flees into the mountains (where he befriends a bear, naturally). With Beck Randall I could create a character who is doing just that (minus the bear, and with a town not too far away). Of course, Beck’s situation is more complicated because he drags his wife and two daughters along for the ride. His reasons for the move, too, have less to do with a love of nature and more to do with spiting his father – and his father, although unnamed, ends up being a crucial piece to the puzzle of trauma that haunts the family.

CA: Let Gravity Seize the Dead fits within the Gothic tradition. What attracted you toward writing your own Gothic?

DD: When I think back on my reading history, the stories and authors I love most fit into the Gothic tradition: Poe, Hawthorne, Shirley Jackson. Flannery O’Connor’s “Southern Gothic” and her use of the grotesque were also very influential on my writing. Even Franz Kafka, while not considered a Gothic writer, has Gothic elements in the way he uses the uncanny, as well as his use of dark and light and those liminal spaces. So I guess I’ve long been an admirer of this mode, which is as much about atmosphere and the psychology of terror as it is about literal monsters. In fact, my body-horror story collection The Dark Will End the Dark has elements of the Gothic. You could say it’s one of my happy zones.

CA: The popularity of horror fiction has surged over the last decade. While “horror” might not be the best term to describe your book, it’s definitely in the neighborhood. Why are so many readers drawn toward horror?

DD: I like that you said that my book is in the “neighborhood” of horror. It’s a good way of describing my attitude toward genre in general. Genres are like a neighborhood, and just as a neighborhood can have a broad variety of residents, they can all exist together in harmony. Considering that my novella has ghostly presences, possible possession, murder, and a mysterious black rabbit that may or may not have human teeth, I think it settles comfortably into that neighborhood, although it’s more folk horror/Gothic – and very interested in using prose style as a tool to unleash the uncanny.

To answer your question about why people are drawn toward horror, I think it’s primal. I’m a Freudian when it comes to believing that our earliest childhood years (up to age 3 or 4) are what most determines the rest of our lives: our psychologies, our phobias, our coping mechanisms, our ability to live in the world. And those early years are when monsters are real, when ghosts and magic actually exist. Our childhood imaginations are live wires, conduits to the magical. I don’t think we ever truly outgrow that. We lose it as we get older, but horror lets us tap into our formative imaginative state.

CA: You write about the natural world with poetic precision. In the Acknowledgments I noticed references to two state parks in Michigan. How does being in nature influence your writing?

DD: For one thing, it creates a meditative state. People like to say that being in nature lets you think, but it’s the opposite for me: when I’m in the woods, my mind is cleared, becoming a blank slate. This is supremely helpful when writing.

In this book and my previous novel, I’m exploring the conflict of how human civilization has pushed us away from the natural world. We’ve moved steadily from our connections to the wildness of nature and have fooled ourselves into believing we don’t need it or aren’t even a part of it anymore. I’m as guilty of this as anyone, and maybe this is why I’m interested in it – there’s a tension there. I feel like I’ve lost a part of myself by choosing a life separate from nature, like some part of myself is dormant and I probably won’t ever be able to bring it to fruition.

The other aspect of nature in this novella is how it retains its story forever. You can read the trees, the foliage, the animals, and learn its traumas, its history. It literally alters itself in response to events like wildfires, deforestation, etc. The natural world is cyclical – evolving and adapting – but on a chemical level it never forgets. I think people are the same way, retaining our traumas on an unconscious level. When I wrote this book I wasn’t aware that there’s a field of scientific study called epigenetics, which posits that people who didn’t actually experience the traumatic events can have their DNA altered by them. Even hundreds of years after the fact, our ancestors’ traumas can change our genetic code. If that’s not a literal “haunting,” I don’t know what is.

CA: Many writers avoid the novella for commercial reasons, but the length seems perfect for the story you’re telling and the way you tell it. Did you set out to write a novella?

DD: I appreciate you saying that, since I did set out to write a novella. Don’t get me started on the issue of what makes a book “marketable” to commercial publishers. It’s a real frustration as an artist to be boxed in by form and content, to be told that this or that isn’t profitable. That’s why I’m so grateful to independent presses like Regal House and Tortoise Books (to name a few of many; and of course literary journals like yours as well!), who are willing to keep the art of writing alive in all of its wonderful possibilities.

I find the novella to be the most potent form of storytelling. The canvas is larger than a short story, which allows more opportunity to build mood, tension, conflict, and character complexity, but it’s leaner and tighter than a novel and retains some of the white hot flame of short fiction. Novellas like Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream, Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams, and Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle were all hugely influential to me.

CA: This is your seventh book. How has your work changed over the years?

DD: It’s pretty surreal that this is my seventh published book. I vividly remember the painful process of trying to get my first book published, when I honestly wondered if it ever would happen. So I never take this stuff for granted.

As for how my work has changed, I hope I’ve strengthened my ability to be concise and clear while maintaining a strong, distinctive presence of voice and style. I remember when my former MFA teacher Jaimy Gordon told me, “You’re a stylist,” and I was so green that I had no idea what she meant. I grew to understand it: prose style and narrative voice have always been at the forefront of everything I write. I embrace this artistic impulse, but I also believe that style should never announce itself more loudly than the story. What I mean is that the reader shouldn’t be distracted by style; the style needs to create the sense that this – the particular way the sentences unfold, the word choice, the rhythm, the beat – is the only proper way to tell this story. It’s like cinematic style. When Martin Scorsese puts in a long 1st-person POV tracking shot in Goodfellas that guides us through an entire restaurant/nightclub, it’s not just eye candy. It’s in service to the characters and plot – showing us the overwhelming, dizzying, whirlwind experience that Karen is having as she begins dating this mobster. It’s not just style for style’s sake.

–

Chuck Augello (Contributing Editor) is the author of The Revolving Heart, a Best Books of 2020 selection by Kirkus Reviews. His work has appeared in One Story, SmokeLong Quarterly, Literary Hub, The Coachella Review, and other fine journals. He publishes The Daily Vonnegut, a website exploring the life and art of Kurt Vonnegut. His novel, A Better Heart, was released in November 2021.

Darrin Doyle is the author of seven books of fiction, most recently the novella, Let Gravity Seize the Dead (Regal House Publishing) and the novel The Beast in Aisle 34 (Tortoise Books). His short stories have appeared in many literary journals. He teaches at Central Michigan University.