When readers think “world-building,” science fiction and fantasy often come to mind. But “other worlds” also exist within the past, and Leah Angstman, in Out Front the Following Sea, has created a world as detailed and intricate as any fantasy. Set in the 1600s, Angstman’s novel is a vibrant historical adventure whose themes are in conversation with current times.

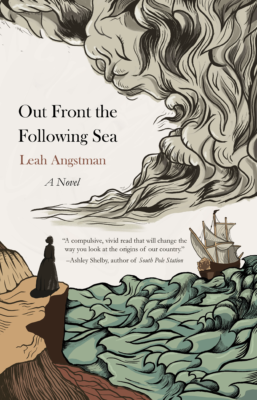

Purchase your copy here.

Angstman recently shared her thoughts with Cease, Cows.

Chuck Augello: How would you describe Out Front the Following Sea to a potential reader?

Leah Angstman: It’s a literary historical action-adventure epic somewhere between a Jack London, Hilary Mantel, James Clavell, Herman Melville, Cormac McCarthy, and Bernard Cornwell. Set against the backdrop of French and English colonial tensions during King William’s War in 17th-century New England, an Englishwoman accused of witchcraft must decide which side of the war she’s really on, and how far she would go to save a Frenchman from the noose. It’s brutal and immersive, action-packed and heightened, darkly humorous yet wrenching; and it’s been called “stunning and masterfully crafted” (Readers’ Favorite), “fascinating, just shy of hallucinogenic” (Scott Phillips), “meticulously researched” (Aline Ohanesian), “simply brilliant” (Ted Scheinman), and “way too violent” (my mom). You should probably read it.

CA: The book’s subtitle is “A Novel of King William’s War in Seventeenth-Century New England.” What interested you in writing about that historical period?

LA: The 1600s are the most fascinating time to me in the annals of European settlement in what would become the United States, and it’s also one of the most overlooked centuries in the brief European history of this country. It was terrifying and wild, and yet at the same time, it was utterly mundane. I think what interests me most about it is its violence and uncertainty. Colonists had been here long enough to say, “Okay, this is happening. We’re here to stay,” but there was still so much uncertainty about the future of everything. Boston and Manhattan were already well established and moving forward briskly, but there were spats and inhumanities, both petty and foundational, all across the colonies (and back and forth to Europe, and definitely among colonists and Native Americans). Communication and transportation were tragically slow, and the only thing certain was that you’d lose most of your children before they made it to their teens, and your death was going to be gruesome from some horrific element that would be entirely unpleasant. These are the dark recesses that fascinate me.

CA: Many readers will be unfamiliar with the history. What challenges does that create for you as the author?

LA: With our knowledge of the 1600s being heavily impacted by The Scarlet Letter and The Crucible and Hollywood’s depictions of witches, Pocahontas, and Pilgrims, people carry into the time period so many preconceived notions about what it was like and how people must have behaved during it. People like to call it “the simpler times,” but they really have no idea how difficult it was, how many different types of people there were, and how those folks interacted with one another. To a lot of people, America was ‘Native Americans, boom, 1776, yay we’re a country’—and that’s it, with no gray area in between. America before, during, and after European settlement was never and has never been a monoculture, yet people somehow can’t bring themselves to believe that there were scientists and atheists; thinkers and readers; pagans and pacifists; feminism and sarcasm; utopian societies; sexual fluidity; whites who fought for the rights of Native Americans; Black people who weren’t enslaved; homosexuals, bisexuals, transgender people (Thomas/ine Hall, an indentured servant in Virginia in 1629 was both male and female intersex, for instance, and wore “men’s” breeches with a “woman’s” apron, 60 years before my book even takes place); colonists who bucked against religious intolerance, sexual repression, and the patriarchy, etc.

We also get so wrapped up in our own narrow focus of the “founding” of this country that we don’t stop to think about what was going on in the rest of the world. The 1600s was a fascinating century the whole world over. In some ways, it was also a more liberated time, too; the world changed drastically during the Victorian Era and became far more prudish and obsessed with taboos, etiquette, class stations, and rules—the layperson is unable to separate the before and after of this, however, because it’s just too far away from us to retain its nuance now.

So, my biggest challenges are preconceived notions. I’ve heard some interesting ideas from reviewers, readers, and my own family. One reader said that the feminism was too modern, as if Marie de Medici, Nur Jahan of the Mughal Empire, Queen Nzinga of Angola, Anne of Austria, Maria Anna of Spain, Sophia von Hanover, et al., were not contemporary feminist rulers, movers, and shakers of the 1600s. Feminism is in no way modern—it’s just much more recorded and visible now. Another reader questioned whether the science is too modern for a character to think about at this time, without pausing to remember that Sir Isaac Newton was a respected, famous, and published contemporary of the period. Science was highly fashionable in 1600s Europe, where New England’s imported goods came from. Copernicus and da Vinci, authors whose books Ruth has in her trunk, were published almost 200 years before my book takes place.

One reviewer questioned Ruth drinking coffee. (Besides the person who takes care of Ruth being a seaman on a merchant trading vessel with plenty of access to what we think of as traditional bean coffee,) nut, root, and berry coffees were common, particularly acorn and holly berry coffee. The word coffee even comes from a Dutch word, and Ruth lives in a Dutch settlement.

Another reader mentioned that the sarcasm sounded modern, as if people didn’t tell jokes since the dawn of man, as if ancient Greek literature from Euripides to Socrates isn’t littered with sarcasm and irony. Humor isn’t some modern invention. Another notion people have is that being angry about land getting taken from Native Americans is some modern thought and that no white settlers in the 1600s (through 1700s) cared about the plight or culture of American Indians. That’s absolutely false. We have several accounts (a good number, considering how few accounts exist from that time period of anything at all) of white settlers who traded with, translated for, lived with, married into, conducted legal work for, had deep friendships with, and fought beside Native Americans. Many, if not most, historians believe the “vanished” Roanoke Colony simply married into and moved in with nearby Native Chesapeake tribes, a hundred years before my story even takes place.

Another reader said that she didn’t think a person accused of witchcraft would still be allowed to live in a town without getting burned at the stake. This notion is Hollywood talking. Everyone loves the stories that are the most extreme; we glom onto the Salem Witch Trials like that was the norm and not the outlier, without stopping to think that the reason we still talk about it and know about it is because it was the outlier. (Massachusetts, as a whole, was an outlier, and my book doesn’t take place in the weird, isolated, unpopular, heavy-handed, puritanical colony that was Massachusetts.) Every town and settlement had people who were suspected of something, town gossips, inhabitants no one liked, people who didn’t fit in, thieves, assholes, drunkards, and philanderers. Humans were still human then as they are now. They weren’t all just driven away and executed. They were ignored and tolerated the way we still dislike roughly 30 percent of our neighbors today.

So, I’ve been thinking a lot about this, and I think the preconceived notions are the hardest challenge I face. The fact that my story isn’t “simple” and dives into some issues that might be controversial, dark, or myth-busting, means that I go up against more readers who don’t want their mindsets swayed or who simply can’t see past their own ideas of what the time period seems like it should be. People who can put those notions aside come along with me for a very epic tale (It’s fiction! Crazy things can happen in fiction!), and people who can’t put those notions aside get hung up on their own beliefs. But. It’s still a wild ride, even if you’re a puritan at heart.

CA: The novel includes maps and an illustration of a ship. Why did you feel that these were important to include?

LA: It’s not so much important to include as it is nice to include. In a land and time that most people are pretty unfamiliar with (and that is somewhat different from how it looks today), I think it helps readers to be able to envision the environment, the landscape, the expanses. This is a time when maps were essential. GPS didn’t exist. No one had smartphones to get around. The story deals a lot with navigation by sea, and sailors lived by maps, log books, and stars. It was the age of property, divisions and lines and borders, and maps depict those property lines in a way that words cannot. More than anything else, maps feel like the 1600s to me, a symbol of the era, a time of navigation, an anchor to the Age of Sail.

CA: Tell us about Ruth, your main character.

LA: During the course of the book, she starts out sixteen and ends up seventeen. Like most teenagers, she’s curious and impulsive, and she’s particularly headstrong, which gets her into a lot of trouble. She’s a victim of her environment as much as she’s an instigator in its unraveling, a product of her time but always bucking against it, just like teenagers today. She’s orphaned at a young age, and all she knows is forward, survival, looking out for herself, so she’s quick to act without thinking of the consequences. She craves friends, adventure, a place to belong. She’s imperfect. She’s sometimes wrong. But don’t expect some kind of frilly YA novel just because she’s a teenager (another challenge I face with this book); in colonial times, she would have been considered an adult, so she’s stuck on that cusp of holding onto childish ways and having to be a responsible adult in the violence of the times.

CA: Each chapter begins with a quote from historical figures like Sir Isaac Newton and Sir Oliver Cromwell. How do these quotes help guide the reader through the story?

LA: The use of quotes is multifaceted. First, each quotation is by a contemporary or predecessor of the time period, so the quotes provide a context that wraps around the timeframe. They are the words of scientists and philosophers, navigators and warlords with questionable morals. They show you ideals and thoughts of the time period, examples of how controversial issues like feminism, racism, religion, and scientific studying are not “modern” conflicts.

Second, continuing the context, they give you actual language and words of the time, a backdrop of thought, a voice that is visual and wraps around the characters’ personalities and existence. The quotations are as much a visual part of the language of the time period as the maps are of the depiction of physical expanses. Third, the quotations set the mood and theme of the chapters, summing up what just happened and where we’re about to go in the language of the time. They act as a bridge.

And fourth, they give you a breath. As a student of theater (one of my myriad other lives before this one), I always carry with me a little piece of Bertolt Brecht into my writing. Brecht always relieved the tension or the action with asides and non sequiturs and the breaking of the fourth wall, to remind audiences that they were watching a show and to keep them from becoming too emotionally invested. It’s just a story—breathe. I’m not necessarily a fan of Brecht, but I carry a piece of him, nonetheless. The quotations ease your catharsis. The book is fast-paced and dark, especially as you get into the thick of spiraling events, so it’s important to breathe through it. Pause at the end of the chapter, allow it to sink in, reflect, move on to the next chapter, and then you’re allowed a break—the quotation removes you from the story, puts you into a moment of reality, draws parallels between the reality and the story, and then allows you to dive back in.

CA: The novel is written in English, yet incorporates other languages, and you include a glossary at the end. Why was it important to use other languages?

LA: There is a note at the end of the book that talks about my use of the Pequot language, so I urge people to read that to know more about my thoughts on it, and yes, there’s a glossary at the back for those who need it. I’ve heard several readers say they didn’t know there was a glossary until it was too late, but that was actually not accidental. I purposely didn’t use footnotes, instead putting the glossary at the back; it’s there if you need it, but you don’t really need it. What’s important to me is that you use context—there is nothing in the story that you can’t figure out if you slow down, soak it in, feel the surroundings.

The use of languages, like everything else, is multifaceted. First, the Pequot, who are the main tribe in my book, were here first, long before the Europeans came and brought a new language. To experience the Pequot language is to experience New England in the 1600s, and to see the clashing and crashing of those two worlds side by side. I want you to hear the language, to hear it as Ruth and Owen would have heard it, to pause through those sections and sound it out, hear the poetry in your head. I want you to know that it was English (and Anglo religion) that murdered this language, and I want you to hear that in your mind. When you read it, I want you to stumble on it, and say, “I don’t know this language—why?” and find the answer that the Native Americans find: the colonists have destroyed it. I want that to sink in: that if things had gone differently, you might know this language. I want you to slow down and respect it when you see it on the page and treat it like its own form of poetry.

The second facet, which spans all the presented languages (mainly Dutch and French), not just the Native American ones, is that I want the reader to remember how diverse we were and are, see how good that diversity can be when it’s respected, how it can work together or work against us, depending on how we let it. Ruth, Owen, the Native Americans, the French military officers, and the reader if he reads carefully, can all understand one another while not using the same tongue—there’s body language, expressions, context clues. I want the reader to think of the language on the page the way he would when presented with a real person who doesn’t speak his own tongue. You get through it, you make it work, you figure it out, you reach an understanding—or you don’t; that’s a response, too. The book is largely about the othering of outcasts, an us-versus-them mentality, one that doesn’t just run colonist to Native American, but also runs colonist to colonist. And of course, the book shows how destructive that mentality is. When we upset that balance of different cultures, races, languages, religions, genders, diversities, for our own selfish reasons, we lose what’s unique about us as humans, but more importantly, what’s unique about us as a community or society, and as an expansive society of collected internal societies all coexisting together.

CA: What sparked your interest in writing historical fiction?

LA: I have loved history my whole life. It’s mostly my biography-devouring father’s fault, but also my elementary teacher Mrs. Jaworski’s fault. She heaped on me The Witch of Blackbird Pond, Johnny Tremain, and The Indian in the Cupboard, and gave me a love for historical storytelling at a young age. In college, I studied colonial American history (and musical theater, of course, because I could never settle on any one thing), and I wrote a lot of papers and did some very exacting, boring research, and while I was always good at it, it didn’t have the poetry that I desired. What I wanted to do was to take that pedantry and stretch its putty into poetry until I had a mix of the literary and the didactic. The challenge is that I love literary prose and lush language but am completely disenchanted by modern people, events, technology, and social settings. I can’t write about what I don’t care about. Thus, by default of my subject matter and interests, my work becomes “historical fiction,” though in my incessant need to make everything more complicated, it really is highly “literary” fiction and would probably appeal to readers of literary and poetic work even more than to those of commercial, mainstream, or generally accepted “genre” historical fiction.

CA: There’s no shortage of ways to spend one’s time. Why do you choose to write fiction?

LA: Writing fiction was a total accident. I just wanted to tell stories, and the poetry that I’d been writing for decades wasn’t quite enough space for me anymore. Then I blubbered my way through a reread of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables when I first moved to California from Boston, and that was the beginning of the end. A lightbulb went off, and I combined the two things I loved most: stories that made me blubber and deep tedious research that fascinated me. The rest, as they say, is history.

–

Leah Angstman is the author of the historical novel of 1689 King William’s War, Out Front the Following Sea (Regal House, January 2022), and serves as editor-in-chief for Alternating Current Press and The Coil magazine and copyeditor for Underscore News, which has included editing partnerships with Portland Tribune, High Country News, and ProPublica. Her work has appeared in numerous journals, including Publishers Weekly, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Nashville Review; and she’s recently been a finalist in the Chaucer Book Award, Cowles Book Prize, Able Muse Book Award, and Richard Snyder Memorial Prize, and longlisted for the Hillary Gravendyk Prize, Goethe Book Award, and Laramie Book Award. She is an appointed vice chair of a Colorado historical commission, an appointed liaison to a Colorado historic preservation commission, a sponsoring member of the Louisville (Colorado) History Foundation, a founding Quartermaster member of the American Battlefield Trust, and a volunteer at her local mining-history museum. You can find her at leahangstman.com and on social media as @leahangstman.

Chuck Augello is the author of The Revolving Heart, a Best Books of 2020 selection by Kirkus Reviews. His work has appeared in One Story, SmokeLong Quarterly, Literary Hub, The Coachella Review, and other fine journals. He publishes The Daily Vonnegut, a website exploring the life and art of Kurt Vonnegut. His novel, A Better Heart, will be available in November 2021. Ingrid Newkirk, founder of PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) calls it, “Lively, engrossing, fast-paced, and spot-on when it comes to nailing what’s wrong with animal abuse but in a realistic, not preachy way. A great read, a great beach novel.”