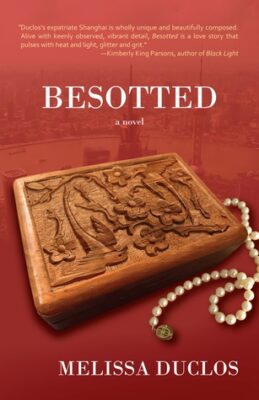

Feel like traveling but can’t afford a trip abroad? If you’ve ever wondered what it might be like to move to China and begin a new life teaching in a foreign language school, Besotted, the new novel by Melissa Duclos, should jump to the top of your reading list. A perceptive exploration of the intricacies of desire, Besotted introduces readers to the landscape and culture of Shanghai along with a vibrant cast of characters and their complicated relationships.

Purchase your copy here.

Duclos recently shared her thoughts with Cease, Cows.

Chuck Augello: If you saw someone at a bookstore holding a copy of Besotted, what might you say to entice them to read it?

Melissa Duclos: If I saw someone I didn’t know with a copy of Besotted in a bookstore, I’d yelp softly and hide behind a shelf, then try to sneak a picture of them holding the book, then run away.

Later, though, on Twitter, I’d say Besotted is a plane ticket to Shanghai, where the neon pulses against a smog-grey sky. I’d tell them it’s a book in which Love comes to life, and can’t be trusted.

CA: The novel is set in Shanghai. What inspired you to write about China and the ex-pat experience?

MD: I moved to Shanghai with my sister when I was 24. I didn’t speak Mandarin (my sister did) and didn’t know much about the culture when I arrived, but I was excited to have a brief adventure abroad. Though I was only there for six months, the city stuck with me. When I returned home, I knew I had to write about it—the smells and noise and the overwhelming feeling I had just walking around a city where I was so obviously an outsider. I started Besotted a few months after I returned to the states, which tells you how long it took for me to finish the book and find a publisher!

CA: Tell us about Sasha, the novel’s narrator. If you were introducing her to someone, how might you describe her?

MD: Sasha is a character in mourning. At the start of the book she’s already lost a family who’s rejected her for her sexuality and two girlfriends who she didn’t know how to interact with because of the shame she’d been made to feel about her desires. And then she lost Liz, too. She tells the story of what happened between them because she wants to know why. The story she tells about her relationship with Liz in Shanghai is both honest and full of assumptions and guesses. She doesn’t always come off well. Sasha is relatable—I think—though not likable. She’s wounded, and only as the book unfolds is she able to really look at those wounds.

CA: Sasha’s interest in Liz is immediate and powerful. What is it about Liz that so strongly captures Sasha’s attention?

MD: When Liz moves to Shanghai, Sasha has been living there for three years. She speaks Mandarin and understands the school bureaucracy, but she’s also depressed, still mourning the loss of her last relationship and her family. Liz, meanwhile, arrives completely unprepared to navigate the city or fulfill her duties as a teacher at an international school. She needs Sasha’s help finding an apartment and writing a lesson plan. It’s this need that Sasha finds so instantly attractive. Sasha’s hope is that if she can make herself indispensable to Liz, she can avoid abandonment.

CA: At times Sasha projects herself into Liz’s consciousness and experience, commenting on things she should have no way of knowing about. Should readers consider Sasha an unreliable narrator?

MD: Sasha projects herself into Liz’s consciousness because she’s desperate to understand why Liz left her. She’s as unreliable, I think, as any other broken-hearted person who obsessively replays their lost relationship in their mind, searching for the explanation they were never given.

CA: The ex-pat Dorian plays a key role in the relationship between Sasha and Liz. Tell us about Dorian.

MD: Of all the characters in Besotted, Dorian is the one who loves Shanghai the most. Liz doesn’t understand the city, and Sasha sees it only as a place to hide from the life she left behind. For Sam, who grew up in Shanghai, the city is a box he can’t escape from. Dorian—an American architect who spends the novel navigating the Chinese bureaucracy to buy a condo—loves the city for its capacity to change and incorporate outside influences. He gives the reader a different view of Shanghai than any of the other characters. He’s also a self-absorbed asshole, but I still have a soft spot for him.

CA: What did you find most challenging about writing Besotted?

MD: I struggled a lot with the perspective. I wanted to write a novel that starts at its end, exploring why, rather than how, things between Sasha and Liz fall apart. I struggled to bring suspense into the book, and to make the question of why matter to a reader. I spent a lot of time figuring out why it mattered so much to Sasha—why the end of this relationship was so devastating to her. Once I decided to use a somewhat unconventional first-person omniscient narrator, I was able to make Sasha’s heartbreak more palpable.

CA: You also publish a newsletter on small presses. Please tell us about it. How can readers sign up to receive it?

MD: I started Magnify a year ago with the goal of highlighting small press books. The newsletter is for readers looking for great, under-the-radar literary fiction and creative non-fiction; writers who are interested in publishing with a small press; and critics who want exposure to venues that publish small press reviews. Each month I highlight four new(ish) reviews of small press releases, give an inside look at some aspect of small press publishing, and share a review of an indie press book that’s at least a year old, written by the owner of the indie bookstore Another Read Through. The experience of putting out the newsletter has been wonderful: I’ve learned about so many authors and presses, and been able to interview publishers, critics, podcasters, and other authors about their work either writing or promoting small press books. There’s a link to subscribe on my website.

CA: If you were given the front page of The New York Times Book Review to promote a writer whose work you think deserves greater attention, who would it be, and why?

MD: This is a REALLY hard question! I read so many small press books that are absolutely amazing and yet get very little in the way of review coverage by major outlets. Rather than choosing one writer, I’d really like to see much more coverage of small press books from 7.13 Books (my fantastic publisher), Forest Avenue Press, Seven Stories Press, Kernpunkt Books, C&R Press, Red Hen Press… I could go on. I’ve completely dodged your question, I know. But I really believe that some of the most interesting new work today is coming from small presses. The New York Times Book Review really couldn’t go wrong giving these publishers more attention.

CA: There’s no shortage of ways to spend one’s time. What inspires you to keep writing?

MD: I don’t know if I feel inspired to keep writing as much as I feel compelled. When I stop writing I become an unpleasant person to be around. It’s the best tool I have for processing my own experiences—either in fiction or essays. I’m working on a collection of essays now about heartbreak and writing and have a new novel about the anxieties of motherhood simmering. I write about what I’m struggling with personally.

–

Chuck Augello (Contributing Editor) lives in New Jersey with his wife, dog, two cats, and several cows that refuse to cease. His work has appeared in One Story, Juked, Hobart, SmokeLong Quarterly, and other fine places. He publishes The Daily Vonnegut and contributes interviews to The Review Review. He’s currently at work on a novel.

Melissa Duclos received her MFA in creative writing from Columbia University, where she was awarded the Guston Fellowship. Her work has been published in The Washington Post, Salon, Bustle, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, and Electric Literature among other venues. She lives with her two children in Portland, Oregon, where she works in communications for a non-profit organization. She is the founder of Magnify: Small Presses, Bigger, a monthly newsletter celebrating small press books, and is at work on her second novel and a collection of humorous journals.