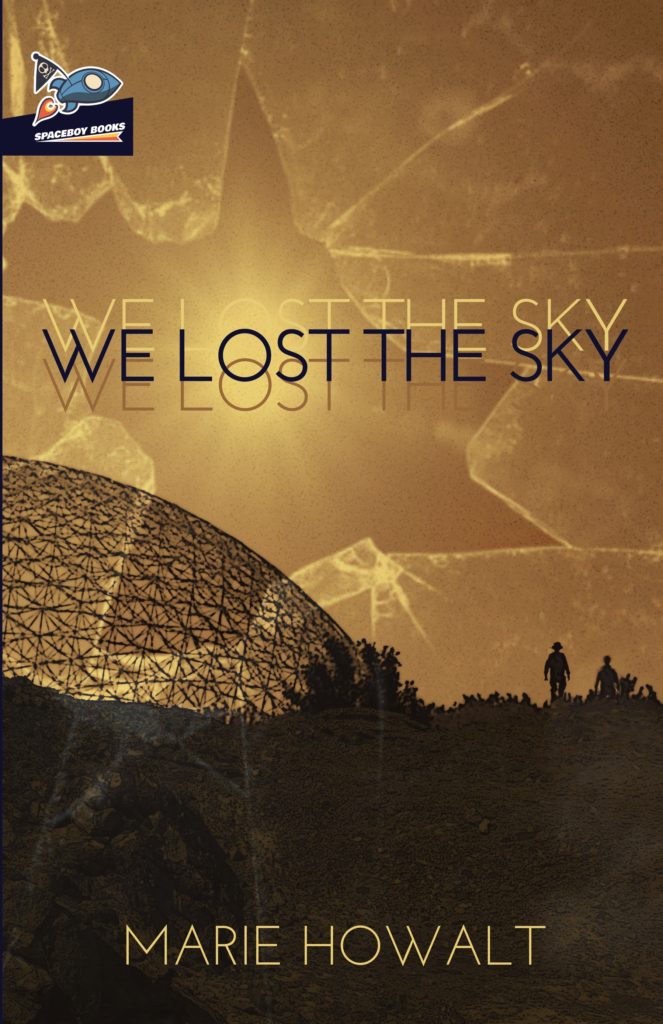

While science fiction and fantasy novels are often set in different worlds, astute readers recognize the connections between the alternate universe, be it one of space or time, and our own troubled world. In We Lost The Sky, author Marie Howalt shows readers a distant future through the eyes of four diverse characters. Sci-fi and fantasy fans should enjoy Howalt’s fast-paced and engrossing debut.

Purchase your copy here.

Marie Howalt shared her thoughts in a recent interview with Cease, Cows.

Chuck Augello: If you came across someone in a bookstore holding a copy of We Lost the Sky, what might you say to entice him or her to read it?

Marie Howalt: After silently freaking out, you mean? Maybe something like, “If you enjoy sci-fi with sarcastic snark, emotional agony, rebellion, and universally human questions all wrapped in a post-apocalyptic character driven adventure in a world far from the one you live in that still feels a bit too close for comfort, this book will be right up your alley!” At which point I’d probably need to breathe before adding, “Also, buying it will support a good cause.”

CA: What was the initial inspiration for the novel? How did the “idea” come to you?

MH: I think the general idea began with a dream, quite literally. I’m usually in hyper-creativity-mode around bedtime and have been since I was a child (if you’re reading this: Sorry, mum and dad), and it spills into my dreams. Often, the ideas that come out of my dreams are absolute rubbish, but I’ve also dreamed of characters, plots, and worlds that I’ve managed to use as portals into stories. This was one of them. But the moment the idea of We Lost the Sky really lodged itself in my mind was on a bus ride home from a writing group meeting. I was looking up at the rising Moon, and the concept of the world as well as the character of Renn took firmer shape. It was a bit like rings in the water, spreading out from that point to include more characters, places, concepts, plot points and so on. Before I began planning the novel in any detail, though, I wrote a short story about Renn that served as a kind of prequel. It also became part of a charity collection published by Spaceboy Books.

CA: The novel follows four characters, starting with Luca, who we meet in the first chapter. Subsequent chapters introduce Renn, Teo, and Mender, with the different chapters named after one of the four characters. Was it your original intention to tell the story from these four different perspectives?

MH: No, to begin with, I only knew for certain that Renn and Mender were going to be narrators. I wanted one or two additional perspectives to balance the story and it was a matter of finding the best candidates, so to speak. The voices needed to be distinct and different from each other and there had to be the potential of tension between them as well as elements that would connect the characters. I knew early on that Luca would be in the story, but I didn’t realize he had to be one of the viewpoint characters or that he would play such an important role as well as have his own storyline. Teo’s role took a little while to figure out too, but the moment I began writing her first chapter, I knew she was the right choice for the view from inside Florence.

CA: One of my favorite characters is Mender, who’s referred to as an “Other” and a “sentient.” Tell us about Mender.

MH: In the world of We Lost the Sky, a company called CerEvolv produced a wide range of artificials categorized as robots, demis, semis or sentients depending on their level of autonomy and self-awareness. Sentients were the top of the android hierarchy and were created to look as human as possible. Unless there was a specific reason to give them male or female characteristics, most artificials were ungendered and used the personal pronoun ‘ne’ (‘nir’/’nem’). Mender is a sentient android. Renn uses the word Other because it’s what his people calls them. Others are part of their mythology, but very few have ever seen them. Before the world changed, Mender worked as a nurse in a hospice. Ne was made for that purpose and along with nir patients, Mender was moved to a location away from the protected city of Florence in the face of the disaster. At some point, Mender lost nir power supply, but, without going into too spoilery territory, ne is reawakened in the beginning of the book. Throughout the story, we get snippets of information about the job and the priorities ne was programmed with. Writing Mender’s point of view was an interesting experience. Ne is probably the only completely reliable narrator I’ve ever written. Everybody else has emotions they don’t understand or won’t admit to themselves or ulterior motives or topics they shy away from. Mender is extremely simple, but in that simplicity is an honesty and self-awareness that makes nem extraordinary.

CA: In addition to the challenges of creating character and plot, We Lost the Sky includes an element of world-building. What are some of the challenges and joys of building a world?

MH: I see world-building as a journey of discovery. For myself and hopefully for the reader too. I start with a general idea and gradually flesh it out and I really enjoy seeing the puzzle pieces begin to fit together. My favorite thing is putting in the little details that make a world appear real and lived in. At one point, Renn muses, “The proverbial talking stone was back in Mender’s hands.” It’s a small thing, but it’s a glimpse into the culture he was raised in, just like saying the ball is back in someone’s court would be in our world. Some speculative fiction favors a lot of exposition and explanation, and while that can be interesting, I personally prefer to spread out the facts about the world and offer information along the way as it becomes relevant in a (hopefully) natural way. As for challenges, I tend to write myself into a, “but if they have X, why can’t they just use that for Y?” or, “if this isn’t common knowledge in this society, how does this person know it?” corner sooner or later. This happened a couple of times in the first draft of We Lost the Sky, so I had to backpedal and fill out some plot holes along the way.

CA: In one of Mender’s chapters, you write “…In a world frantically preparing for disaster, for changes so immense that no one could predict what would happen with certainty…” Considering the news regarding climate change, this could be our world someday soon. Were the dangers facing our world in 2019 an influence while you were creating the world of We Lost the Sky?

MH: I wouldn’t say that I wrote it with one specific danger in mind. But the idea of radical changes, whether it’s because of manmade or natural disasters, is definitely a central theme. I was preoccupied with how individuals and societies survive, cope, and adapt for better or worse in the face of environmental chaos. I probably sound a little vague here, but without going in full Roland Barthes mode and declaring the author dead, I’m hoping that readers will take something away from the story that speaks to them. Just like writing is a journey of discovery for me, I hope reading the result will be too.

CA: Teo plays an interesting role in the narrative. Tell us about her.

MH: At first, Teo was going to be a different character altogether, but I quickly found that the book needed the point of view of someone who got involved in the events in Florence early on and who would have a lot at stake. I don’t think I’m revealing too much by saying that the four narrators cross paths at some point in the novel. However, Teo is isolated for quite some time. She is idealistic and adventurous and really interested in the ancient technology which is practically forbidden in Florence. She has to deal with being the daughter of an unprogressive politician whose religious and social views are at odds with her own. So in a way, Teo’s storyline is about personal development and emancipation. Her story is the central one because it pulls the others together.

CA: You were born and raised in Denmark and grew up an avid reader of science fiction and fantasy. Are their big differences between Danish sci-fi and American? Who were some of the authors that you read growing up?

MH: The biggest difference is that Denmark doesn’t have much of a science fiction tradition at all. When I grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, there was a science fiction subculture and some fan groups, but it was not something I ever encountered as a child. In fact, I can’t think of a single science fiction book written by a Danish author that I read before high school. So the sci-fi I grew up with was a bunch of translated books. I read several of Ray Bradbury’s works (my favorite was The Martian Chronicles), H.G. Wells, and Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day and a lot of not quite as famous books like the YA fiction by Robert Westall and German space opera by Mark Brandis (whose books have not been translated into English, I think). I started writing when I was 11, which was also around the time I watched Star Wars and Star Trek for the first time and found Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy book series. The fifth installment, Mostly Harmless, had not been translated into Danish when I discovered it a bit later, so it became the first novel (that wasn’t intended for learners) I ever read in English. And I just kept going after that, reading more and more sci-fi and fantasy in English, eventually ending up writing the thesis for my Master’s degree on speculative fiction. Nowadays, we do have quite a few Danish science fiction writers. The first one I read was Svend Åge Madsen’s See the Light of Day (Se dagens lys in Danish). He’s probably one of the most well-known Danish sci-fi authors.

CA: Finally, what do you find appealing about working in the science fiction genre?

MH: I generally prefer writing speculative fiction of one kind or another. I have dabbled in alternate history, urban fantasy, high fantasy, and magic realism before. Some of these are waiting for me to edit them while others were published as serialized fiction online. It appeals to me that I can conjure up a world and tell the story I want to tell in that setting, trying to make it the best possible setting for that particular tale. I also really like the layers you can have in sci-fi. It can be an entertaining story, a world different from the confines of mundane reality that readers can dive into, but it can still harbor elements that are relevant to that reality or offer a new perspective on it. It can be a great mix of escapism, entertainment, and commentary on contemporary matters. Science fiction can also be a great game of “what if” and an interesting attempt at predicting where we are headed, in terms of science as well as society.

–

Chuck Augello (Contributing Editor) lives in New Jersey with his wife, dog, two cats, and several cows that refuse to cease. His work has appeared in One Story, Juked, Hobart, SmokeLong Quarterly, and other fine places. He publishes The Daily Vonnegut and contributes interviews to The Review Review. He’s currently at work on a novel.

Thank you very much for a very inspiring and informative interview!