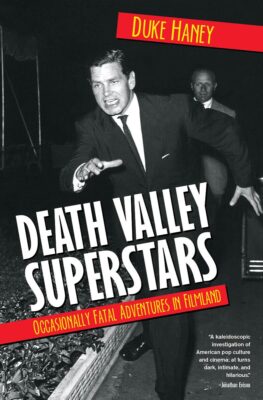

If you care about American culture, Duke Haney’s Death Valley Superstars is a must-read—an intelligent lament for the diminished magic of American films that avoids sentimental nostalgia while capturing both the glamour and the seediness of a vanished world. Though Haney has spent most of his adult life working in the film industry, this isn’t a memoir or a “tell-all” account of his encounters with the famous and the nearly-so. The essays in Death Valley Superstars look beyond the surface to find the sad, tragic, funny, hopeful, and sometimes crazed buried heart of American culture, then and now. Reading Death Valley Superstars in 2019, older readers will recognize many of the names and films Haney references; younger readers will be introduced to a wealth of history that’s important to appreciate and understand so as to make sense of current times. Above all, this is a smart book that engages with its subject matter with affection and insight. If somewhere in the back of your mind you suspect American films could be more than just Aquaman and the latest Pixar cartoon, Death Valley Superstars is the book for you.

Purchase your copy here.

Haney recently shared his thoughts with Cease, Cows.

Chuck Augello: The book begins with a description of the Paramount Theater in Virginia, the type of old-time movie palace rarely seen today. Our local AMC, the only nearby place to see a film, resembles a Sam’s Club more than a theater. How do you think the setting in which we view a film contributes to the experience of viewing the film itself?

Duke Haney: Oh, a great deal. It’s the same with music. I can’t begin to tell you how many bands I’ve seen, and if a show is memorable, the atmosphere of the venue is part of the reason. Atmosphere is what palaces like the Paramount contributed to the moviegoing experience, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that film began to lose its cultural primacy when the multiplex took over. The experience of seeing a movie was no longer special. There was nothing inspirational about it—but I was inspired, as a child, every time I passed the Paramount, let alone entered it. People have no idea what they’re missing in an era indifferent, if not hostile, to atmosphere, which can’t be found on a phone. Nor can it be manufactured. Rather, atmosphere accrues, and almost as soon as it manifests, the wrecking ball appears.

CA: In “When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth,” you relate current-era Hollywood to the classic Twilight Zone episode “It’s A Good Life.” I couldn’t agree more, but many of our readers might be unfamiliar with that episode. Can you tell us about it, and why you think it captures what the film industry has become?

DH: Well, “It’s a Good Life” is about an autocratic child with magical powers, so that he can read minds and transform people into toys and so on; and “When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth” is about the decline of mature movies and the simultaneous rise of juvenile blockbusters, and it seems to me that contemporary culture is being held hostage by the boy of that episode. I view it as a much bigger problem than I indicated in “Dinosaurs.” Superhero movies, or most fantasy-based movies of any kind, are fine for kids, but when adults prefer them overwhelmingly to movies made for adults, it’s clear that ours is a culture of arrested development. There are coloring books for adults, who dress like kids, and read novels written for kids, and talk like kids—Like, I feel like, you know, like—and now we’re dealing with the political consequences. Americans have long prided themselves on their childish “innocence,” rejecting European-style sophistication as elitist, but we’ve taken it to decadent and dangerous levels recently, and I believe Hollywood, or Hollywood since it was reconfigured by George Lucas and Steven Spielberg in the late seventies, bears some of the blame—perhaps most of it.

CA: You’ve worked with the legendary Roger Corman. How did you first meet him?

DH: I like that you refer to Roger as “legendary.” I agree, of course, but most people now have never heard of Roger Corman. I met him because I was hired, over the phone in Brooklyn, to star in a movie that he was going to produce in L.A. I boarded a plane immediately, and was picked up at LAX by a production assistant who drove me first to a wardrobe fitting, then to Roger’s office in Brentwood. It was surreal, partly because it all happened so fast, and partly because of the culture shock; Roger’s office was very L.A., sunny and pristine, whereas I was used to darker, grubbier surroundings in New York. Also, I knew Roger from his TV-talk-show appearances, when he would talk about discovering Jack Nicholson and Robert De Niro, and now he was anointing me, in a sense. I worked for him, off and on, for eight years, and my single regret is that I didn’t preserve his notes about the many scripts he commissioned me to write. They were always concise, practical, and written by hand on the blank sides of discarded documents. Roger was as penurious as his reputation, so naturally he wasn’t going to waste paper.

CA: In “Room 32,” you write about arranging a séance in a hotel room once occupied by Jim Morrison of The Doors. It’s a funny piece—apparently a good psychic is hard to find. Why did you choose Morrison as your subject, and are there any other persons you’d like to contact from the hereafter?

DH: No, I did my one; that’s enough, thanks. I would never have thought to write about Morrison, except that I posted, on a whim, an unusual photo of him on Facebook—it was taken when he was an overweight, short-haired film student at UCLA—and it got such a reaction, I thought, Well, if he’s that popular, maybe I should do something about him for the book. He was a tough subject because, like Marilyn Monroe, so much had already been written about him, but then I had an epiphany: I could hold a séance at his old residence in West Hollywood, which struck me as a unique approach and one he might have appreciated. Also, I knew nothing about the occult world, and this was a chance to explore it. I wouldn’t say I became interested in the occult as a result, though it may have helped to spark an idea for my next book. Then, too, researching Morrison led to my piece about Lee Harvey Oswald: Morrison had written about Oswald in his poetry collection, The Lords and the New Creatures. It intrigued Morrison, as a cinephile, that Oswald was arrested in a movie theater, so I decided to write about Oswald from a film-centric perspective, having always wanted to do something with the JFK case and finally possessing what I regarded as an original angle.

CA: Zabriskie Point, directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, was considered an “important” film when it was released in 1970, but it’s rarely mentioned these days, and I’d venture that now only hard-core film buffs make the effort to view it. Mark Frechette was one of the stars of Zabriskie Point. What inspired you to write about him?

DH: I consider that piece part of a trilogy about semi-obscure actors of the 1960s, even though the pieces aren’t presented as a trilogy in the book. The others are about Christopher Jones, who was touted as the second coming of James Dean and had a psychotic break that was triggered, he claimed later, by the Manson murders; and Sean Flynn, who was discovered at the funeral of his father, Errol Flynn, and switched to photojournalism after starring in a few movies, vanishing in Cambodia during the Vietnam War. Mark Frechette’s story is equally dramatic: he was an apprentice carpenter, with no interest in being an actor, when he caught the eye of a talent scout, and he subsequently joined a cult and robbed a bank as a “revolutionary act.” I thought, taken together, those three stories said a great deal about the sixties, which fascinate me. Jim Morrison and Sly Stone are two more representatives of the sixties, but I wrote my pieces about them after I had planned the others. If I had to choose my favorite pieces in the book, I would probably go with the “trilogy,” though I feel a little queasy about “Pluto in the Twelfth House,” the one about Mark, for reasons I can’t identify. Maybe it’s because I’m ambivalent about Mark as I’m not about Sean Flynn and Chris Jones. The latter did some terrible things—I didn’t even include all of what I learned about him—but I can forgive him because he was out of his mind, and he had by far the most compelling screen presence of the three.

CA: You write with great insight about Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and other figures of “old” Hollywood. It’s hard to imagine any of today’s film stars achieving the same kind of iconic status. Why do you think that is?

DH: Good question. First, people don’t care about film stars the way they used to do. The young care about YouTube “stars” and the characters played by this or that actor, Spider-Man and Batman and so on, more than the actors themselves. The two women you cite had extraordinary sex appeal, a term seldom heard now that almost nobody embodies it, male or female, onscreen or otherwise. Sex appeal is finally a product of charisma, not beauty, contrary to the rhetoric of literalists and ideologues; and to the extent that charisma is developed, not innate, it can’t be developed in a world where people have surrendered so much of themselves to tech devices. If Marilyn Monroe had lived in the age of Instagram, I’m sure she would have wasted her gifts on selfies, and no selfie will ever endure as Monroe’s collaborations with top photographers have endured. Then, too, the Internet is intrinsically opposed to mystery, and mystery is a key component of charisma, which people are no longer capable of recognizing, it’s so scarce. Tom Hardy evoked Brando somewhat in the early phase of his career; now he might as well be a computer-generated effect in movies filled with CGI, movies he elected to do. I skimmed a story about him recently that presented him as a “Hollywood rebel.” Yeah, right. The last Hollywood rebel was marched into the desert and shot in the head years ago. A sense of danger, which usually accompanies rebellion, is another key component of charisma, or as I write in the book: no friction, no fire. But even if such figures existed in the twenty-first century, I think they would seem too threatening to be admired. We deserve our Kardashians, Biebers, PewDiePies, and so on.

CA: As a writer, you’ve written across genres: screenplays, novels, essays. What surprised you the most about the difference between screenwriting and writing prose fiction?

DH: With screenplays, characters serve the plot. With prose fiction, the plot is determined by the characters, or it is the way I work. Also, characters in novels are deeper and more detailed than they are in screenplays, and there’s a lot more description of places, objects, and states of mind. Reading screenplays is a chore for most, especially in Hollywood, where people scarcely read at all, and since description, perceived as discursive, adds to the chore, it’s best kept to a minimum. Even when they’re written well, screenplays are akin to fast food, whereas I aim to prepare a banquet in writing a book, fiction and nonfiction alike.

CA: If you had to recommend only one of the many films you’ve worked during your career, which one would it be, and why?

DH: None of them! But pressed to pick one, I would go with Life Among the Cannibals, a black comedy that was made in 1996 with the independent-film market in mind. Because of hits like Reservoir Dogs and Clerks, there was such a market at the time, though it was already ebbing and Cannibals was never released in the U.S. It’s an irreverent movie that, as the director used to say, takes shots at everyone, and I would shriek with laughter while working on the screenplay. I’m in it also. But I haven’t watched it in a long time, so I can’t vouch for it, and I “recommend” it only because it seems like Citizen Kane compared to so many other productions with which I am lamentably affiliated.

CA: Hopefully Death Valley Superstars will find a wide audience. What are you working on next?

DH: I write toward the end of Death Valley Superstars that I only began it because I was unable to make progress on a novel. Gradually I realized that the novel was, in fact, two novels, two separate stories, but I couldn’t altogether determine which elements belonged to which story, until I had a revelation in late 2016. It was really a series of revelations: I lived almost in a daze while one of the novels unfolded over the course of a month or so, and I would scramble to take notes, sometimes getting out of bed or dashing out of the shower to grab a pen or hit the keyboard, whichever was nearest at hand. But I had to finish Death Valley Superstars before starting the novel, and now I have to rest and collect myself. I hinted already that the book deals with the occult, however peripherally and ambiguously. Its working title is XXX, and while that will probably change, it might provide a clue as to another of the book’s subjects.

–

Chuck Augello (Contributing Editor) lives in New Jersey with his wife, dog, two cats, and several cows that refuse to cease. His work has appeared in One Story, Juked, Hobart, SmokeLong Quarterly, and other fine places. He publishes The Daily Vonnegut and contributes interviews to The Review Review. He’s currently at work on a novel.

Duke Haney, aka Daryl Haney, has spent most of his adult life working in the movie business, with twenty feature-film credits as an actor and twenty-two as a screenwriter. He used pseudonyms for some of the screenplays and went by “D. R. Haney” as the author of a novel, Banned for Life, and an essay collection, Subversia. After he was struck by a car in a crosswalk on Sunset Boulevard, a friend claimed he walked like John “Duke” Wayne and gave him the nickname by which most people know him and he has taken belatedly as his pen name. He plans to follow Death Valley Superstars with a novel tentatively titled XXX.