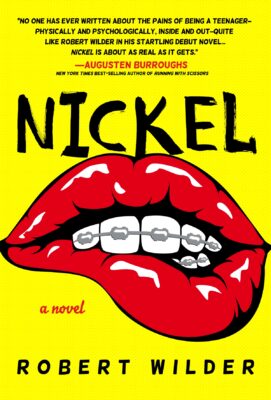

Adolescence is a time of heightened emotions, an awkward and exhilarating age when everything feels fresh and newly discovered. It’s a time when no two words carry as much meaning as “best friend,” and when we first learn to navigate the challenges of the heart. Robert Wilder, in his new novel Nickel, explores these challenges with insight and wit. He shared his thoughts in a recent interview with Cease, Cows.

Chuck Augello: Why did you title the book Nickel?

Robert Wilder: Without giving anything away, the novel is centered around a teenager’s best friend getting a mysterious illness and nickel (the metal) may have something to do with it. But I also thought about how something like nickel (the coin) can be so hard and yet have a certain beauty and value. In my years of teaching, I’ve seen how teenagers can seem so hard or tough, but there’s always something valuable about them and something they value if they dig deep enough.

CA: Describe the relationship between Coy and Monroe, the novel’s two main characters.

RW: Coy and Monroe are the oddballs or misfits in a large public school. They band together to survive and develop a tight friendship based on similar tastes in music and pop culture, as well as a recognition of how the other suffers. They also develop their own vernacular—a type of code only the two of them understand. Even though their code can be funny or seem harsh, it’s a way of trying to protect themselves, process hardship, and understand a difficult (and beautiful) world.

CA: Coy and Monroe are fans of the 1980’s, and the novel is packed with pop culture references. What about the Eighties resonates so strongly with these teens?

RW: I’ve seen many students who were simply born in the wrong decade. Some should have followed The Grateful Dead on their European tour in 1972; others should have been 1950s greasers or swing dancers in the thirties. A good number really love the 1980s and know much more about movies and songs from that era than they do about early American history. I recently wrote something on Foreigner, a band Coy and Monroe are obsessed with, and I saw that eighties music had this range that extended from hard rock-and-roll to cheesy love ballads. Films had the same range during that time. I think all of us want permission to exhibit the full spectrum of human behavior and that decade somehow allows that.

CA: Early in the novel Monroe develops a mysterious illness. How does that change Coy’s relationship to her?

RW: Coy has had a rough life. His dad died and his mom is in a type of rehab facility; he’s not the coolest kid in his teen community. Once he befriends Monroe, he finds a way to navigate all these challenges. So when Monroe gets sick, all bets are off. He’s terrified of losing her, but he’s also terrified of losing whatever stability he’s accomplished with her by his side. So much of his life has been about loss. Once Monroe falls ill, things get even more complicated for Coy, including his feelings.

One of the hard realities he faces is that having only Monroe as a friend has saved him from isolation, but her friendship has also limited him. Monroe puts a hard edge on almost everything. I see that as a coping mechanism and a way for a young woman to protect herself in a tough world. Since she is such a dominating force, Coy is not able to fully express himself. When he meets Avree, she sees a different side to him and gives that side acknowledgment and encouragement. This new friendship puts Coy in a bit of a quandary—if he embraces Avree, he feels disloyal to Monroe.

CA: One of my favorite characters was Coy’s stepfather, Dan. Tell us about him.

RW: Dan is based on a lot of really well-intentioned yet ill-equipped parents, stepparents, and adults I’ve watched as a teacher and known as a friend, as well as my own insecurities about being responsible for other humans. I’ve seen adults marry into families and believe that the biological parent has everything under control, so they can take it easy in a way. If you have kids, you know nothing and no one is ever completely under control. And a stepparent or partner can be left with someone else’s child and that’s a huge responsibility, especially if you are still somewhat of a child yourself.

CA: Nickel is narrated by Coy. What were some of the challenges in writing in the voice of an adolescent?

RW: When I started Nickel, many of the kids I was thinking about spoke in code and sound effects, so my early drafts were an attempt to try and emulate that manner of speech. When I sent the manuscript to my friend Christopher, he said, “This is great but totally unreadable.” So I had to try to keep the core elements of Coy’s voice but allow the casual reader access to him and his world. Another challenge of a voice like this is that there is no such thing as “the teen voice;” the same way there is no such thing as “the adult voice.” Every state, town, school, class, friend group, and individual has their own way of speaking. My own students’ slang changes and evolves daily. Coy’s voice is his own and reflects who he is, where he comes from, and what’s ahead of him. That’s all.

CA: Nickel should appeal to both teens and adults. Why do you think YA fiction attracts so many adult readers?

RW: I’m not sure. People far smarter have different takes on this. Like me, many writers want to spend time with teenage characters and don’t consider how to categorize their work as they compose. When I started Nickel, I just wanted to write the most honest portrayal of Coy and Monroe (and their world) that I could. When I finished, my early readers kept asking me “Is this literary fiction or YA?” To be honest, I hadn’t really thought about it. The publisher’s job is to sell books, so they decided to market it as a YA crossover, meaning it could speak to both adults and teens. That seemed fine until I traveled to a booksellers’ convention to pimp Nickel and a bookstore owner said, “I’m tired of hearing about crossover; tell me about the crossunder.” That’s when I knew that writing is my business far more than selling.

CA: What are some of your favorite novels featuring teenage characters?

RW: Obviously, The Catcher in The Rye, Jo Ann Beard’s brilliant In Zanesville, The Outsiders, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime by Mark Haddon, PUSH by Sapphire, The Patterns of Paper Monsters by Emma Rathbone, Diary of a Teenage Girl by Phoebe Gloeckner, Stitches by David Small, Donkey Gospel by Tony Hoagland (poetry) and others.

CA: Are you working on another novel? More essays?

RW: I finished a novel last year that I hope to sell soon. I’m also working on a television pilot loosely based on my two earlier books, Daddy Needs a Drink and Tales From The Teachers’ Lounge. I’d love to take a crack at writing the screenplay for Nickel if that’s at all possible. Essays are never far from my mind as well.

–

Chuck Augello (Contributing Editor) lives in New Jersey with his wife, dog, two cats, and several cows that refuse to cease. His work has appeared in One Story, Juked, Hobart, Smokelong Quarterly, and other fine places. He publishes The Daily Vonnegut and contributes interviews to The Review Review. He’s currently at work on a novel.